Sarah Ryan is a reporter and anchor at Global News Edmonton. This is her first-person account.

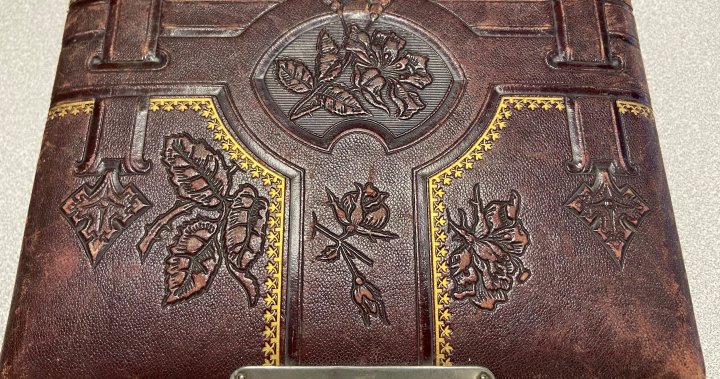

For more than a year, I’ve been trying to discover the secrets behind a mysterious antique photo album delivered to Global Edmonton.

It arrived at the TV station in 2023 — with no note, no return address and no context.

The album is full of sepia photos, many of which were taken in Scotland. How they ended up at a news station in Edmonton… I set off to find out.

Many of the photos are posed, portrait style images, clearly taken in studio. Others are candid, amateur pictures depicting life on the Prairies.

First, I thought perhaps the book had been stolen. Perhaps the thief had a change of heart and was returning it to a safe space. But Edmonton police didn’t have any reports of missing antique photo albums.

So then, I thought I’d bring the album to a local photography expert: Fay Cunningham, from the Antique Photo Parlour at West Edmonton Mall.

“For the age of it you know, it’s in really good condition,” she said, her eyes lighting up as she turned the album over in her hands.

She’s been taking professional photos for nearly half a century. She flipped through the pages, analyzing each image and explaining how much photography has changed over the decades.

Nobody said “cheese” back then and dental hygiene wasn’t a priority. Cunningham said there’s also another reason everyone looked so serious back then.

“To smile in a photograph was to be thought a fool. You want to be considered sort of sophisticated.”

She believes the the oldest images are from the late 1800s and were taken in studio by a skilled photographer.

Back then, portraits were expensive and usually only taken for special occasions, such as weddings.

Based on their clothes, Cunningham believes the family was wealthy.

“With those gowns, sometimes it was really awkward to sit,” she said, pointing to photos of women standing in elaborate dresses.

Get daily National news

Get the day’s top news, political, economic, and current affairs headlines, delivered to your inbox once a day.

“They weren’t made out of polyester so they creased really badly.”

Cunningham said they also had to make do with natural light sources.

“They didn’t have lights, they didn’t have flash. So they would use a northeast window and people would have that light on the side of their face. They would have a neck brace and a back thing to stand in to hold them,” she explained.

“An exposure could be, depending on the sun of the day, like two to three minutes — so you wouldn’t dare to move.”

I also reached out to Barbara Isherwood, an art history lecturer at the University of Toronto.

She believes the album is a late Victorian photo album, which contains “carte de visite” images, which were passed around to friends and neighbours “rather like trading cards,” Isherwood said.

“They were affordable and hugely popular. Everyone from royalty to merchants had them made.”

There are other hints, not just in the photos themselves, that help date the images.

A business card of sorts, embossed on the photo mats, includes the photographer’s name, the address of their studio and its logo.

“In those days, that was an advertisement to say, ‘this is me and this is where you can come get your photo taken,’ ” Cunningham said.

I found a website that documents Victorian photographers from Glasgow, Scotland.

Some of its sample images have identical calling cards to those in our mystery photo album.

Unfortunately, there are no contact options for the website creator.

I reached out to our talented IT specialist to see if the metadata might reveal who’s behind the website, but no luck. They did not want to be found.

Some of the website’s information though, leads me to believe the oldest photos in this album are from the 1880s, making them around 145 years old.

But it’s not just the Scottish portraits that make this album so intriguing.

Cunningham and I also took a closer look at the newer photos in the album, likely from the 1910s-1920s.

There are multiple pictures of horses and farmers fields.

“All this harvesting? This is a whole ‘nother time in history for these people,” Cunningham suggested.

The images appear to show a Prairie landscape. Our thought? The family immigrated to Canada, bringing this album with them.

There are snapshots of children, too.

“This is somebody with their little point and shoot camera,” Cunningham explained.

Then I found two names written on the back of this photo of two young girls: Lillian and Hellen Shipp.

Photo Album Mystery.

Sarah Ryan / Global News

That clue led me to reach out to Claudine Nelson, with the Alberta Genealogical Society.

Volunteers there used those names, and this photo of Sunnyfield Farm, to trace the Shipp family back in history.

Photo Album Mystery.

Sarah Ryan / Global News

The Genealogical Society connected me to a woman with the last name Shipp, but her husband has long since passed away and she didn’t know anything about any album.

Unfortunately, her husband’s family also wanted nothing to do with it or Global’s story. They didn’t even care to see it.

Antique photo albums like this aren’t worth much financially. It’s the family’s memories within that are valuable — the snapshots of days gone by.

“I would say that could be why you got this. Because nobody in the family said, ‘those are really important to me,’” Cunningham said.

While the album clearly isn’t of significance to the Shipps, it is to those who strive to preserve history.

The Edmonton Archives has already expressed interest in keeping it and Global News intends to donate it.

© 2024 Global News, a division of Corus Entertainment Inc.